Cobden Exhibition 2015

This online exhibition marks the 150th anniversary of Richard Cobden’s death in 1865. It is based around the changing public and private image of Cobden during his own lifetime, from his early days as a Manchester business man, via his emergence as a major national politician during the campaign against the Corn Laws, to his maturity as a statesman with an international reputation. It also looks at some of the ways Cobden was commemorated after his death and how his legacy endured.

We are grateful to the Centre for Culture and the Arts at Leeds Beckett University and the University of East Anglia for sponsoring this exhibition.

1.Cobden c. 1830, artist unknown

©Manchester Archives.

When this portrait was painted, Cobden was just establishing himself as a Lancashire businessman. His bullish spirit at this time is revealed in a letter to his father: ‘if you were to strip me naked & turn me into Lancashire with only my experience for a capital I should make a large fortune’ (10 Aug. 1831: Letters, i. 39). Cobden’s commercial success was the foundation of his career as a local, then national politician, but his business was a casualty of the anti-corn law campaign.

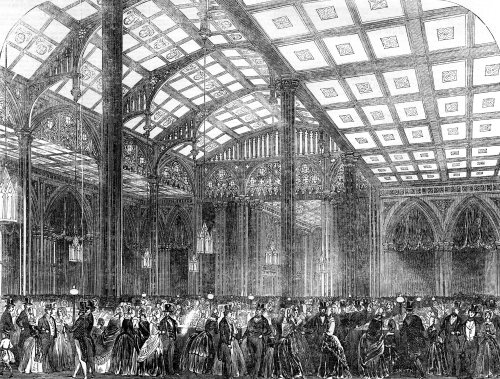

2. The great Anti-Corn Law League Bazaar, Covent Garden, Illustrated London News, 17 May 1845

© Illustrated London News/Mary Evans Picture Library

Cobden will always be associated with the great movement against the Corn Laws. The Anti-Corn Law League became the most efficient propaganda and fund-raising machines of the age. It also pioneered the involvement of women as political fundraisers, notably through its use of ‘ladies sales’ or bazaars. The greatest was at Covent Garden in 1845, which raised the equivalent of almost half a million pounds in today’s money. Shortly before it opened Cobden wrote to his wife: ‘I went to see the model of the Bazaar Hall which is being prepared in Covent Garden Theatre . . . It will be a Gothic Hall 150 feet long & 40 feet high– lighted from above on the outside of the roof– so as to give it the effect, through the transparent & painted linen roof of being covered with glass & the sun shining upon it– The effect will I should say be very glorious & novel’ (16 April 1845: Letters, i. 386-7).

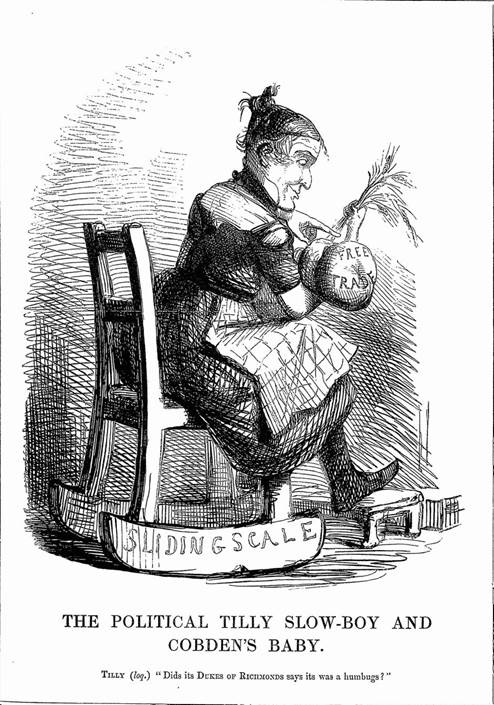

3. Punch, 31 Jan. 1846: courtesy of Leeds Central Library.

Reproduced with permission of Punch Ltd.; www.punch.co.uk

One of several cartoons by John Leech satirising the Prime Minister’s conversion to the need for Corn Law repeal. The images often featured a feminised or infantilised Peel supposedly acting under Cobden’s influence: here he is nursemaid to Cobden’s ‘baby’ (actually a free trade loaf). Tilly Slow-Boy was a comic character from Dickens’s Cricket on the Hearth, illustrated by Leech. Peel’s praise of Cobden in his resignation speech in June reinforced the connection between Cobden and repeal in the public mind.

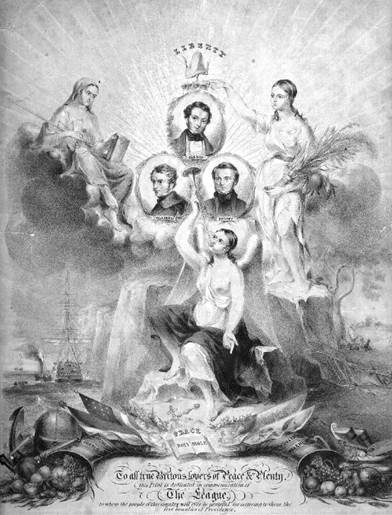

4. Commemorative Anti-Corn Law League Poster, 1846.

© Manchester Archives.

While Cobden gained much of the credit for repeal, there were also efforts to remember other contributors to this long campaign. This poster shows Cobden being crowned with the cap of liberty, surrounded by the fruits of free trade and supported by fellow campaigners John Bright and Charles Villiers. Villiers had proposed an annual motion against the Corn Laws in parliament, and Cobden conceded to Joseph Parkes that ‘I have trod upon his heels, nay almost trampled him down, in a race where he was once the sole man on the course’ (18 July 1846: BL Add. MS 43664, fos. 13-16).

5.Sunderland-ware commemorative plaque of Cobden, c. 1846:

courtesy of Stephen Smith and Ian Holmes. http://www.matesoundthepump.com/

A huge range of objects were created for the popular market after repeal of the Corn Laws. Many featured images of Cobden, usually based on a portrait by Charles Allen Duval. Cobden was now synonymous with Corn Law repeal, as he described in a letter to George Wilson: ‘the faith must be incarnated, and hence I have been chosen, here, for the embodiment of the free trade doctrine’ (11 July 1846: Letters, i. 448). Cobden may have been a saleable asset, but his activities over the succeeding decade would test this popularity to destruction.

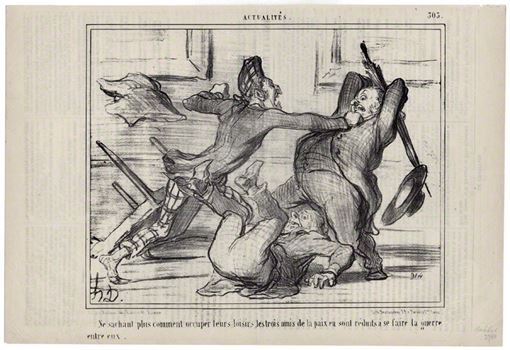

6.Lithograph, by Honoré Daumier, 1856,

© National Portrait Gallery, London.

Cobden saw free trade between nations as a step towards universal peace: by making war unprofitable, he hoped to make it unthinkable. The Crimean War of 1854-6 saw him increasingly out of step with public opinion, and he admitted to George Combe that ‘I will vote for peace on almost any terms as preferable to the present purposeless & sanguinary war.’ (9 Dec. 1854: Letters, iii. 64). Public hostility to Cobden extended also to Britain’s ally, France. In this French cartoon the conclusion of the war means that Cobden (left), Bright and fellow peace campaigner Joseph Sturge have nothing else to do but to fight among themselves.

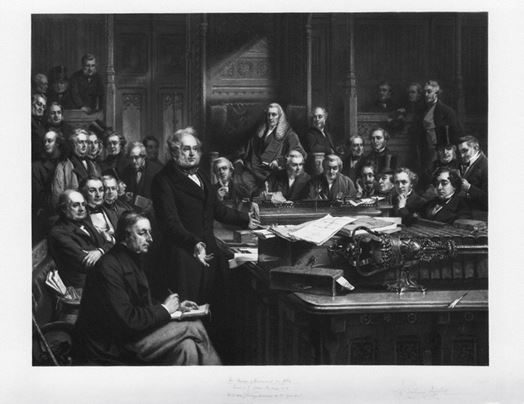

7.‘House of Commons debating the [Cobden-Chevalier] Treaty, 1860’,

by Thomas Barlow, after John Phillip, 1862 or after. © National Portrait Gallery, London

In 1860 Cobden’s reputation underwent a revival when he negotiated a ground-breaking commercial treaty with the French government, paving the way for a network of such treaties which, for a time, saw free-trade values adopted across much of Europe. This official painting commemorating the debate on the treaty suggests that the government were wholeheartedly in support of Cobden’s efforts, but that year he wrote from Paris to the President of the Board of Trade (Thomas Milner Gibson) complaining that ‘all the foul play, – annoyance, lies, & obstacles, I have had to encounter from the first have come from your side of the Channel’ (30 Sept. 1860: Letters, iv. 106).

8. Richard Cobden at Dunford House, W. Sussex.

© Manchester Archives.

Cobden’s earliest years were spent on his father’s farm, Dunford, in West Sussex, until the family were evicted in 1811. In 1847, with the proceeds from a national testimonial, Cobden was able to purchase Dunford and refashion it as a small country house. This became his retreat from Westminster. After his election defeat in 1857 he wrote to Joseph Parkes: ‘I am in no hurry to get back to the House [of Commons].– When I saw the other day that [it] sat till ½ p[ast] 4 I hugged myself & looked out on the South Downs with a keener relish’ (28 July 1857: BL Add. MS. 43664 fos. 81-4).

9.Statue of Cobden by Marshall Wood, St Anne’s Square, Manchester, 1867.

Courtesy of Dr Simon Morgan

The statue of Cobden in St Anne’s Square, Manchester, was unveiled in 1867. The procession to the square reinforced Cobden’s credentials as a popular hero by including trade and friendly societies, and harked back to the anti-Corn Law campaign by parading the big ‘free trade’ and small ‘protectionist’ loaves: a tactic the League had used in the 1840s. Other statues were erected in Salford, Stockport, Camden Town and Bradford. The Camden Town statue was paid for largely by Emperor Louis Napoleon, while that in Bradford Wool Exchange was funded by an American merchant eager to commemorate Cobden’s defence of the North during the American Civil War.

10.Rue Cobden Richard, Cognac,

courtesy of Prof. David Brown.

The presence of Streets named after Cobden in European towns is testament to his positive international reputation in the nineteenth century. In Britain, Streetmap.co.uk lists 266 streets named after Cobden. Many of these are streets built on land belonging to the National Freehold Land Society, or its regional variants. Cobden was a great supporter of this organisation, which eventually became part of the Abbey National Building Society in 1944. Its original purpose was to parcel up estates into 40 shilling freehold plots which could be balloted for by shareholders. The aim was partly political: to increase the number of (hopefully Liberal) working class voters eligible to vote in county elections.

11. Photograph of (Emma) Jane Catherine Cobden Unwin by Cyril Flower, 1st Baron Battersea, c. 1890s:

© National Portrait Gallery.

Cobden was survived by five daughters, his son Dick having died in Germany aged 16. Of the five Anne and Jane Cobden became the most politically active, Anne as a socialist and Jane as a Liberal. Both felt they were carrying on and defending their father’s legacy. Jane (pictured) espoused a range of Liberal causes including Irish Home Rule and Land Reform, opposed the Boer War, and supported women’s suffrage. In 1888 she became one of the first women to be elected to the London County Council. Intriguingly, she has achieved something of a strange afterlife as a central character in the BBC’s Ripper Street drama series!

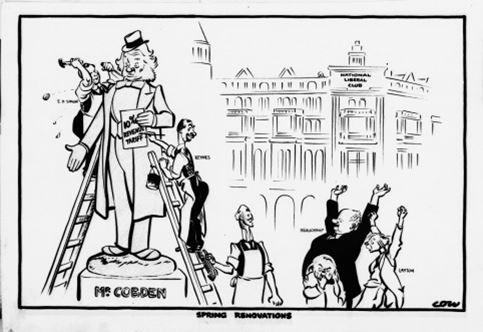

12.David Low ‘Spring Renovations’, cartoon, Evening Standard, 16 March 1931:

© David Low/Solo Syndication

In the early twentieth century, supporters of free trade increasingly invoked Cobden’s name as they fought a rearguard action against the encroachment of protectionism. Here cartoonist David Low satirises John Maynard Keynes’s proposals for a 10% ‘revenue tariff’ in 1931. The following year, Neville Chamberlain, Chancellor of the Exchequer in the National Government, would finally put paid to free trade as official British policy, signalling a retreat into protectionism and the promotion of ‘imperial preference’. The abandonment of free trade led to a general amnesia about Cobden, particularly after the Corn Law debates slipped from the School curriculum.

Richard Cobden aged c. 26: ©Manchester Archives and Local Studies.

Woodcut illustration of the great Anti-Corn Law League Bazaar, Covent Garden, Illustrated London News, 17 May 1845: © Illustrated London News/Mary Evans Picture Library

John Leech, ‘The Political Tilly Slow-Boy and Cobden’s Baby’, Punch, 31 Jan. 1846: Reproduced with permission of Punch Ltd.; www.punch.co.uk.

Anti-Corn Law League poster: © Manchester Archives and Local Studies.

Sunderland-ware Plaque of Richard Cobden: © private collection.

Honoré Daumier, lithograph cartoon of Richard Cobden, Joseph Sturge and John Bright, 28 April 1856: © National Portrait Gallery.

Photograph of Cobden at home, c. 1864: © Manchester Archives and Local Studies.

‘The House of Commons debating the [Cobden-Chevalier] treaty, 1860’, by Thomas Oldham Barlow, after John Phillip, 1863 or after: © National Portrait Gallery, London.

Statue of Richard Cobden by Marshall Wood, Manchester, courtesy of Dr Simon Morgan.

Rue Cobden Richard, Cognac, courtesy of Prof. David Brown.

Photograph of (Emma) Jane Catherine Cobden Unwin: © National Portrait Gallery.

David Low ‘Spring Renovations’, cartoon, Evening Standard, 16 March 1931: © Solo Syndication/Associated Press.

)