Q&A with Prof Thomas Ruys Smith: The legend of Santa Claus

By: Communications

We’re coming up to the time of year where Santa Claus will be coming down people’s chimneys and leaving presents (or coal!) under their trees.

It’s something so ingrained in pop culture, with countless Christmas songs and movies referring to the figure.

But where did the legend come from?

Prof Thomas Ruys Smith from UEA’s School of Politics, Philosophy and Area Studies, and author of Searching for Santa Claus: An Anthology of Poems, Stories and Illustrations that Shaped a Global Icon (Boiler House Press, 2025), sat down with us to answer some questions.

Where did Santa originate from?

Santa Claus first started delivering presents in America in the late eighteenth century, but the first time that he appeared in print was in 1821.

A storybook for children showed him arriving in a sleigh pulled by reindeer, dressed all in red, before leaving presents in stockings.

People started telling more and more stories about this generous Christmas visitor and, inspired by what they read, Victorian British children in the 1850s started hanging up their stockings for Santa Claus too.

What is the difference between Santa Claus and Father Christmas?

Father Christmas has been around a lot longer than Santa Claus. A version of Father Christmas called “Sir Christmas” featured in a fifteenth century carol, and Father Christmas himself was appearing regularly in print by the seventeenth century.

At first, Father Christmas was just a personification of the season. Most often depicted wearing a crown of holly, he represented wintry weather, feasting and drinking with friends and family, and a generally merry spirit of Christmas celebration.

But, at least to begin with, he didn’t have anything to do with stockings.

When Santa Claus became popular with Victorian children, slowly but surely Father Christmas started to push back on the American’s grip on the nation’s stockings.

So, he started helping out with the business of delivering presents, dressing a bit more like Santa Claus, and by the dawn of the twentieth century, the two figures had become virtually interchangeable and shared the load of making sure everyone’s stockings were full up on Christmas morning.

How do other cultures interact or represent Santa Claus/Father Christmas?

Of course, other countries have wildly different ideas about who brings their Christmas presents each year.

The saint’s day of St Nicholas on 6 December has long been the occasion for gift-giving in a number of European countries, particularly the Netherlands.

He arrives in mid-November on a steamboat from Spain, where he lives.

Other saints also serve as festive gifters – in Greece and Cyprus, Saint Basil does the honours on New Year’s Eve, while Saint Lucy brings presents to Italian children on 13 December.

Of course, it’s not just saints who perform this important role. In other parts of Italy, the task falls to Befana, a witch who distributes goodies on the eve of Epiphany. In Spain, the Apalpador pats the tummies of sleeping children to see how many chestnuts to leave them.

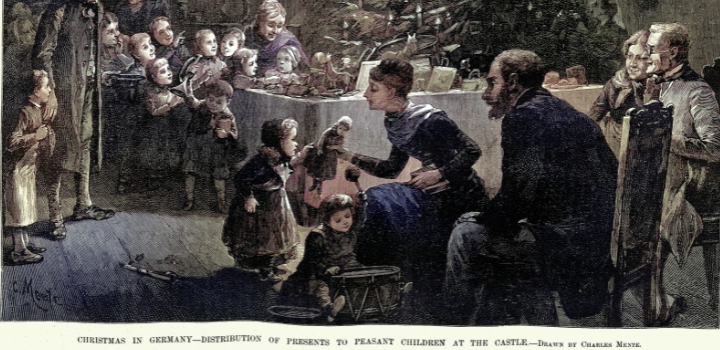

Germany boasts a plethora of festive gift-bringers and their companions, from the angelic Christkindl to the threatening Belsnickel, draped in furs and carrying a stick to beat those not deserving of gifts!

Iceland has a similarly scary range of seasonal characters: the ogres Grýla and Leppalúði, who cook children in a large cauldron, and the Yule Cat who devours those who fail to procure new clothes before Christmas Eve.

And some are just annoying: the Yule Lads, thirteen mischievous boys who threaten domestic chaos across the festive period, licking your spoons and stealing your candles.

Santa is a much safer bet.

How has the legend expanded across the years?

What’s really unique about Santa Claus amongst Christmas gift-bringers is that after the essentials of his legend had been established in the 1820s, writers and artists slowly built him a whole world, one with which we’re all very familiar.

By the middle of the nineteenth century, they’d introduced us to his home in the snowy north.

Next came the construction of his toy workshop and his army of elf helpers. When the illustrator Thomas Nast started producing annual portraits of Santa Claus for Harper’s Weekly in the 1860s, Santa’s distinctive appearance also started to become settled.

Mrs Claus followed in the 1870s, though no one has ever conclusively decided whether or not the couple have any children.

Poet Clement Clarke Moore named all of Santa’s reindeer as early as 1823, but Rudolph was a late addition to the team, arriving in 1939.

L. Frank Baum, the author of The Wizard of Oz, tried to rename them in 1902, starting with a pair named Flossie and Glossie.

Unsurprisingly, it didn’t stick. Still today, new versions of Santa’s story try to change our understanding of his inner and outer lives – sometimes they add to his legend, sometimes they’re forgotten, but either way, he’s still a character who inspires storytellers.

What are the biggest changes from the beginning of the legend to today?

Probably the scope of his operations! Santa Claus started out as a figure associated with the New York region.

As his legend grew, he became a figure familiar to all Americans by the 1850s. It was soon after that he went international.

A poem from 1857 depicted Santa Claus travelling the world on a global present delivery route, and it was certainly about that time he crossed the Atlantic and became a favourite with Victorian children.

Thanks to his use in Christmas advertising over the past century or so, Santa is a figure who is now recognised around the globe.

Santa has also always been open to the use of new technology. When the telephone and the camera started to become popular in the nineteenth century, for example, Santa was quick to incorporate them into his operation, and the impact of new technology on present deliveries is still a popular theme for Santa stories today.

If there’s one thing that I learned from editing a book of the most important Santa Claus stories and illustrations, it’s that his legend has always been in flux. He has been the inspiration for artists and writers for centuries.

But at the centre of the story, there’s also something essential and unchanging about Santa and the domestic rituals that we’ve constructed around him.

When you hang up your stocking this Christmas Eve, you’ll be doing so in the same seasonal spirit of hope and excitement as children two centuries ago.

Watch Prof Thomas Ruys Smith talk about how Santa came to be so well-known in pop culture below:

Related Articles

New book reveals evolution of Santa Claus legend

A new book by an academic at the University of East Anglia (UEA) offers readers a rare glimpse into the literary and artistic origins of one of the most beloved figures in popular culture.

Read more

UEA and Redwings launch ‘kindness to animals’ pledge inspired by Black Beauty author

A new animal welfare pledge has been launched by Redwings and the University of East Anglia (UEA) to honour the legacy of Anna Sewell, the author of Black Beauty.

Read more

"We're all Scrooge now": What the Victorians still have to teach us about Christmas

With the cost-of-living squeezing households and charitable giving in decline, a University of East Anglia (UEA) expert says we could all learn a thing or two from the Victorians.

Read more