Jean McNeil is Reader in Creative Writing at UEA and the author of 14 books of fiction, non-fiction, poetry and essays, including Ice Diaries: an Antarctic Memoir (2018). Jean reflects on the isolation she experienced on the white continent and how it prepared her for lockdown, and her imagined version of a pandemic versus the real event we are living through.

In the early days of lockdown I undertook an expedition from my desk to the coffee maker. On the way I was seized by a vivid yet abstract feeling, a bit like déjà vu, but with an echo of panic. Why did the unfolding pandemic feel so familiar? Then I remembered: I had written the exact scenario I was experiencing in my novel The Ice Lovers, published over a decade ago. Until that moment on the way to the Nespresso machine I had completely forgotten this.

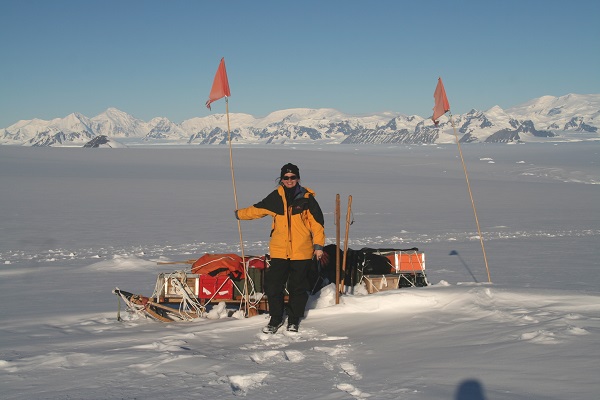

The Ice Lovers was the result of a year-long writing residency with the British Antarctic Survey. I researched it during a nearly five month-long stay on the continent; on bases, ships and planes; and in the Falkland Islands, BAS’s logistics hub in the Southern Ocean.

Antarctica was a thrilling, lethal jail. To live on an Antarctic base is an extreme state of siege – probably its closest corollary is being an astronaut. If we went outside to walk or ski we had to do so in Handmaid’s Tale twosomes. We were forbidden to go more than 300 metres away from base on our own; the last person who disobeyed this rule and went for a scenic walk misjudged the shoreline and fell into icy water, nearly killing themselves.

That year, at the end of the Antarctic summer, we waited for the relief ship, the RRS Ernest Shackleton, to collect us and take us back to what we called the ‘real world’. The ship was scheduled to arrive around the end of March, before the sea ice froze, after which ships would not reliably get through. Those early winter days began to take on a surreal schedule. We lost an hour of light every day. Wildlife – whales, penguins, skuas – began to dissolve from the seas and skies around us, heading north to warmer climes.

In the middle of March we received worrying news. One of the Shackleton’s engines was on the blink and the winds in the Drake Passage were blowing 50 knots. Our rescue – called ‘uplift’ in Antarctica – began to look doubtful. If the ship couldn’t get to us, would we have to stay until the following October, when the ice broke up and ships could once again get in? That was seven months away. In between stood the total winter of Antarctica. More frightening than minus 40 and three months of total darkness was the possibility of being marooned with 21 over-winterers (personnel who remain on base all winter) who had already mentally said good riddance to us. As it turns out, hell is not eating frozen cheese and powdered milk for seven months, but other people.

In those early lockdown days, I had to force myself to read the passages of the novel again. What would be worse – if I’d gotten it wrong, or right, in terms of my accuracy of a horrible event? In the novel the pandemic scenario is a backstory. It takes place in London, four years before David and Helen, two of the main characters, travel to the white continent. In Antarctica they experience echoes of their confinement four years before, cowering in their flats as a virus erased ordinary life.

Alone and entrapped in her north London flat (based on my own home) Helen observes the dog walkers: ‘I saw them, sometimes, in the wedge of gritty green that passes for a park… they wore white masks and looked around them, constantly, as if they could spot it coming.’ She notes the ‘stiff choreography’ of people avoiding each other ‘like dancers in a Merce Cunningham piece.’ Airports are shut, and – just as I still look into the sky for planes threading through the waypoints to Heathrow – she finds she ‘missed that sound, of hydraulics, the groan as the plane’s bellies slit open and the landing gear dropped down, more than I ever would have believed.’

After the novel was published, I regretted the pandemic scenario – wasn’t it too claustrophobic and terrifying for readers to engage with? Why did I choose that route in plot, characterisation, narration?

We were eventually plucked from the Antarctic, two weeks later than planned and within days of our departure becoming operationally impossible. In so-called lockdown I recently re-read my diary from those weeks. Alongside a list of things I missed from the ‘real world’ (swimming, films at the BFI, espresso) was a declaration: ‘I realise I am built for the world, meaning the outside world, all its random aggression and inanity and mortal glamour.’ The last phrase – mortal glamour – is what the antiseptic, controlled space capsule of the Antarctic somehow short-circuited, despite being glamorous in its own spectral way.

Now, the equation between the Antarctic, climate change and a pandemic is obvious. It goes something like this: the coronavirus has emerged in part because of environmental degradation and abuse of animals, which has pushed previously separate species into a hostile proximity. Capitalism has declared war on nature, and one of the results is climate change. Global heating is fuelling the disintegration of the great ice continent moored at the bottom of our planet; Antarctic ice will one day submerge Piccadilly Circus. Climate change will also activate previously frozen pathogens, unleashing future pandemics.

Antarctica is at once the safest place to be in a global pandemic, and also a permanent state of lockdown. As I orbit my north London flat, I find I have become a character in my own novel. Helen’s passage, imagined over a decade ago, are my thoughts now: ‘So we have to live with house arrest, it might last a month, two months. I stood so many times… my hand on the sliding balcony door. Only the vision of myself in a hospital bed, or worse, at home in my own bed, putrid, bloated and decomposing, stopped me from opening it.’ What I didn’t render in the novel is how time feels undifferentiated, like wading through sludge, the vicious bouts of internal anger at how the loss of life and economic wastage could have been avoided.

My time in Antarctica was very much like lockdown life: mostly iterative. While our field trips into the interior of the continent were astonishing, on base we saw the same people, the same interiors, the same views, day after day. Those weeks we spent waiting for the ship as the continent congealed around us feels much like my current existence. The pandemic scenario was born in Antarctica during my final days on base, even if I didn’t know it at the time.

Her four months hunkered down as a pandemic overtakes London does not change Helen profoundly. She scours herself for the enlightenment trauma can bring, but discovers that ‘I just wanted to go on living, as I had before the sickness.’ Like her, intellectually I might want to re-tool the world from the cocoon of my fortunate confinement, but I also long for Pandemic World to release us from its grip, and for the return of Ordinary World – plane travel, hugs, pub lunches – in all its mortal glamour.

:focus(1858x1749:1859x1750))