|

|

|

Outreach

NERC Planet Earth

|

Sky News - The wind of change

|

New Scientist - Earth's windiest region confirmed by crewed flight

|

Times Online - Weather mission to Greenland

|

PhysOrg - Professor explores Greenland's impact on

weather systems

|

Eastern Daily Press - Team mission to forecast

with greater accuarcy

|

Vancouver Sun - Physicist to ride Greenland's winds

|

Eastern Daily Press - Team mission to forecast

with greater accuarcy

By Tara Greaves |

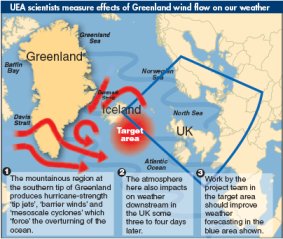

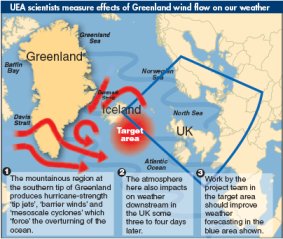

| Don’t know why there’s no sun up in the sky? Blame Greenland’s weather. UEA experts are on a mission to “significantly improve” the accuracy of British weather forecasts – and they believe looking closely at weather patterns in the mountains of southern Greenland may hold the key. They will take to the skies in a specially-adapted aircraft this week to attempt to gauge the influence of the atmosphere over both Greenland and Iceland on the weather in Britain and northern Europe. In particular, they believe the mountainous region in the southern tip of Greenland produces hurricane strength “tip jets”, “barrier winds” and “mesoscale cyclones” which turn the seas and affect the weather downstream in the UK some three to four days later. |

|

|

Small cyclones known as “polar lows” can sometimes produce heavy snow in north-western Europe. The pioneering research, led by Ian Renfrew of UEA’s School of Environmental Sciences, comes at the start of the International Polar Year which begins on March 1 and is launched in the UK by the Princess Royal on February 26. “In Britain, we tend to view medium-range weather forecasts with a certain scepticism, so it is very exciting to be part of a project which could significantly improve their accuracy,” said Dr Renfrew. “Though we have suspected for several years that the mountainous presence of Greenland has a strong influence over our own weather, this will be the first time that its impact has been observed.”

|

|

|

Dr Renfrew and an international team of scientists – drawn from the UK, Canada, Norway, Iceland and the United States – will conduct the Greenland Flow Distortion Experiment (GFDex) from February 21 to March 10. Richard Swinbank, who is leading a team from the Met Office, said: “We will identify areas where additional targeted observations should be particularly beneficial, and afterwards we will check the benefit that the extra observations had on our forecasts.” As well as improving predictions of UK weather, the research will also fill in missing gaps in the existing climate change models, such as those used by the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) in its major report earlier this month. This will help to improve the accuracy and the long-term range of climate change predictions. |

Vancouver Sun - Physicist to ride Greenland's winds

U. of Toronto scientist pumped for some serious storm chasing

Margaret Munro

CanWest News Service

Monday, February 26, 2007

KEFLAVIK, Iceland -- Flying into hurricane-force winds in a small jet 30 metres above frigid heaving seas is not everyone's idea of fun. But Kent Moore is pumped for some serious storm chasing. The 49-year-old atmospheric physicist from the University of Toronto is here to ride the winds that scream around the southern tip of Greenland at upwards of 180 kilometres an hour. Until now, no one had the nerve -- or perhaps even the desire -- to fly into the "high impact" weather events that help make Greenland one of the most important and forbidding places on Earth. That changes this week as Moore and his colleagues usher in the International Polar Year (IPY) with a three-week field campaign. The International Polar Year is a global effort, involving thousands of researchers, to better understand the polar regions and officially starts March 1. The Greenland Flow Distortion Experiment, or GFDex, is one of the first projects.

Moore and more than 20 atmospheric scientists from Europe and North America are here for a first-hand look at the pivotal, but still poorly characterized, Greenland winds and storms that help power global ocean currents and shape weather in much of the Northern Hemisphere. The researchers have set up a makeshift weather office in a hotel, which is fed real-time data from satellites and weather balloons being released for the experiment by several merchant ships now crossing the North Atlantic from Europe to Greenland and Newfoundland. The British and European weather services are also helping. They're running detailed climate models enabling the scientists to better track storms, winds and "big red blobs," as team leader Ian Renfrew, of Britain's University of East Anglia, describes the huge swaths of the North Atlantic that are almost devoid of weather data. When things get really interesting, the scientists head for the airport to strap themselves into a British research plane, FAAM, short for Facility for Airborne Atmospheric Measurements. Sensors and cameras stud the exterior; banks of machines, computers and monitors have replaced most of the seats inside. It costs $5,000 a day to have the plane and its crew here, and another $5,000 an hour for the 17 reconnaissance flights researchers hope to make. The scientists are particularly intrigued by "tip jets" -- intense winds that race along the icy coast and around Cape Farewell. The winds are so intense they lift vast amounts of heat out of the ocean, cooling the water that then plunges to the deep ocean, helping drive the conveyor of global ocean currents. |

|